Share Post

What can we learn about medical education from activists in other fields? Where does staying woke fit within the curriculum?

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.Maya Angelou, Caged Bird

In the first of her autobiographical books, Maya Angelou brings scenes from her childhood vividly to life: the entrenched, everyday racial discrimination of the American South; the chaotic, sometimes traumatic, life with her mother in Missouri; and her coming of age in California:

caught in the tripartite crossfire of masculine prejudice, white illogical hate and Black lack of power.

Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Her school education made society’s expectations clear:

we were maids and farmers, handymen and washerwomen, and anything higher that we aspired to was farcical and presumptuous.

Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

She describes her gradual realisation that this was not how things had to be; and that she had the ability to change the way things were:

I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.

Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

She went on to become a civil rights activist, raising consciousness of the gap between how things were, and how they could be; and should be.

In my work, in everything I do, I mean to say that we human beings are more alike than we are unalike, and to use that statement to break down the walls we set between ourselves because we are different.

Maya Angelou

Her messages of hope, understanding and reconciliation reached out through her writing, her teaching and her activism, achieving worldwide influence and catalysing social reform. She composed and read On the Pulse of the Morning for President Clinton’s inauguration, while President Mandela read Still I Rise at his own inauguration.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.Maya Angelou, Still I Rise

Many artists in other fields have also tried to open our eyes to the ways of the world. In works such as Five Day Forecast, Then and Now and Twenty Questions (A Sampler), for example, Lorna Simpson uses the medium of photography to explore some of the same themes as Angelou.

More recently the need to see the world as it truly is, and to act to improve it, has been embodied in the concept of staying woke—beginning in African American culture, popularised by the Black Lives Matter movement, but subsequently adopted by many other groups.

Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.

Nelson Mandela

This process, of opening eyes and guiding responses, of awakening and emancipation—a process of education—should be a vital part of medical education. But where does staying woke fit within the medical curriculum? In a short lecture on diversity? As an optional humanities module? Or should it permeate the whole course? And which theories of education can help us with these questions?

Ever since Douglas Adams revealed that the answer—to Life, the Universe and Everything—was in fact forty-two, I have been somewhat sceptical about universal theories: those that claim to provide simple solutions for complex, pan-dimensional issues. Peter Jarvis attempts just such a distillation of educational theory in Towards a Comprehensive Theory of Human Learning. He suggests that teaching and learning can ultimately be reduced to two essential components: the same two components that I have been exploring in this post.

Firstly, there is the creation of disjuncture, a dawning awareness of a yawning fissure between perception and actuality—between a learner’s inner world and real life, or between historical, current and potential realities—this is the way things really are; this is the way they have been; this is the way they could be.

Then, there is the reaction engendered in the learner by this realisation—guided and modulated by their teacher—what Jarvis calls their action tendency. Often, their response does not lead to learning: they have no motivation to change; they retreat from, or downplay the gap; or they are overwhelmed, the gaping chasm just too wide to bridge unaided.

Jarvis believes there are only three action tendencies that result in learning. These map well to Daniel Pratt’s first three perspectives on education, which I explore in other posts: a ritualistic tendency that leads to pre-conscious learning in a Transmission Perspective; non-reflective learning through a repetitive tendency, in a Developmental Perspective; and a creative tendency resulting in reflective learning, in a Nurturing Perspective.

Two of the action tendencies that Jarvis dismisses as leading to non-learning can also become valuable, however, if they are managed well by a supportive teacher. In the preventive tendency, learners want to change but learning is blocked by authorities—the gatekeepers in an Apprenticeship Perspective—who control access to learning. A teacher can help to remove these blocks, which exclude the learner from the community of practice, welcoming and validating them as an integral part of the community.

Of most relevance to this post, in a rebellion tendency the individual recognises a gap, but identifies the cause of the problem as the world outside, rather than something within themselves: “I’m OK—it’s everyone else that needs to change.” Again, Jarvis believes this is harmful to learning; but viewed from a Social Reform Perspective, this response can be seen to be extremely valuable: rebellion becomes a valid educational objective, and revolution a desirable aim.

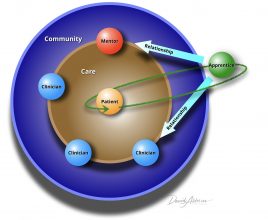

My picture tries to illustrate this last perspective from a healthcare point of view. The teacher, in red, has now become an activist. Their role is to surface shared values, with the learner and others. They encourage the learner, in green, to take on the role of activist too: using these shared values to shine a light on problems and inequalities and empowering them to act to change the situations they uncover. The teacher helps them to negotiate the gaps they find, equips them for the journey and provides sustenance and encouragement.

If the dominant force in other educational models is centripetal, in Social Reform it is centrifugal—acting on the world of healthcare and the wider society in which it is situated.

One example of this perspective is the increasing involvement of doctors in Quality Improvement: giving those at all levels the tools and the remit to identify issues and to make changes for the benefit of patients. Again, in-situ simulation is a powerful way to surface latent safety problems and to license clinicians to effect change.

However, in a large organisation like the NHS there are many areas of practice over which you seem to have little influence. My life as a consultant became much easier after a few years, when I stopped trying to change quite so many things. And there have certainly been times when the immensity of the transformations needed, and the resistance encountered, have meant that I have had to get small—for my own mental equilibrium—and return to my primary role of making a difference, here and now, to the single person in front of me.

But Angelou speaks of both the ability, and the responsibility, of every individual to make a difference on a wider stage; the sphere of potential change extends far beyond the immediate healthcare environment. Doctors are in a privileged position to identify inequality and unfairness in society; and they have a duty to influence cultural change by speaking of the truths they find, both to the powerful and to the oppressed.

Lift up your faces, you have a piercing need

For this bright morning dawning for you.

History, despite its wrenching pain,

Cannot be unlived, and if faced

With courage, need not be lived again.Lift up your eyes upon

The day breaking for you.Give birth again

To the dream.Maya Angelou, On the pulse of the morning